As a writer of both fiction and non-fiction I’ve been asked how I compartmentalise my brain when it comes to finding inspiration.

“How do you know whether an idea will result in a blog piece / article, or a story? I mean, they’re completely different types of writing, right?”

Erm…not really. Oh, sure, I know that writing about reincarnation and magical beings clearly isn’t what you’d call conventional copy, unlike anonymised data and the value of terabit storage. However, even once you get past the requirements of grammar, spelling and punctuation, there are other shared conventions.

1. The writing has to meet the needs of its audience in terms of information, tone and relevance.

2. The writing has to obey the logical conventions of the genre (I’m calling non-fiction a genre today).

3. You need to deliver on your promises.

Examples? Certainly, step this way.

Your headline deliberately provokes a reaction and the subheaders suggest you have pertinent answers to your core question. But you skirt around the issue and end up leaving your readers high and dry.

You write a fantasy novel, where a magical ring can save the good guys, but each time it’s used one of their kin has to die. All the way through the book there have been noble sacrifices, until our two heroes are there, unarmed, cornered by marauding orcs / wizards / demons. Never fear, they can use the magical ring – only which one of them will survive to tell the tale? Imagine how peed off you’d be if no one died (oh, just me then…). You might feel as though you’d been cheated.

Writing for children and young adults places further demands on the writer. Mostly, there are happy ever afters, but that hasn’t always been the case. The shadowy heart of many traditional ‘fairy’ stories is well-documented, despite the Disney cinematic versions that have all but replaced them in popular culture.

Should we though, sometimes, just tell it how it is?

Let’s face it, Disney Studios are unlikely to option The Old Curiosity Shop; not without substantial rewrites, anyway. The fabulous writers, Jacqueline Wilson and JK Rowling, are just two authors among many who allow children to experience some of life’s harder lessons on the page.

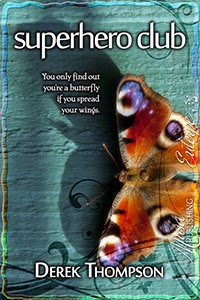

When I came to write my mid-grade ebook, Superhero Club, I spent some time considering why children and young adults read books. Here was the list I came up with:

– Escapism.

– Wish fulfilment.

– Looking for answers.

– Curiosity.

– The enjoyment of a good read.

– Permission to experience experience.

Once I’d met my main character, 12 year-old Jo, and understood what the story was about, I realised I had a duty to show the shadows of her world and to accurately portray the ugliness of bullying and its impact on lives. As the plot developed and secondary characters found their way into the spotlight (that’s how it worked in my head), I also saw how friendship and self-acceptance were the shining threads in the tale. It was important that the story wasn’t too preachy, although I wanted Superhero Club to include the following messages:

– It’s never the victim’s fault and there are positive things they can do.

– Hope.

– Everyone has a story, a reason for what they do, even if we never get to hear it in detail.

– There aren’t always easy solutions.

– We are more than our circumstances, whatever they happen to be.

Today I’m being interviewed about Superhero Club over at Sharon Ledwith’s blog. To be in with a chance of winning a free copy, pop over this week and leave a comment.

I think I found it comforting to read about children having difficult times when I was a child, it was a way to relate. I think these things you've pointed out are great things to keep in mind!